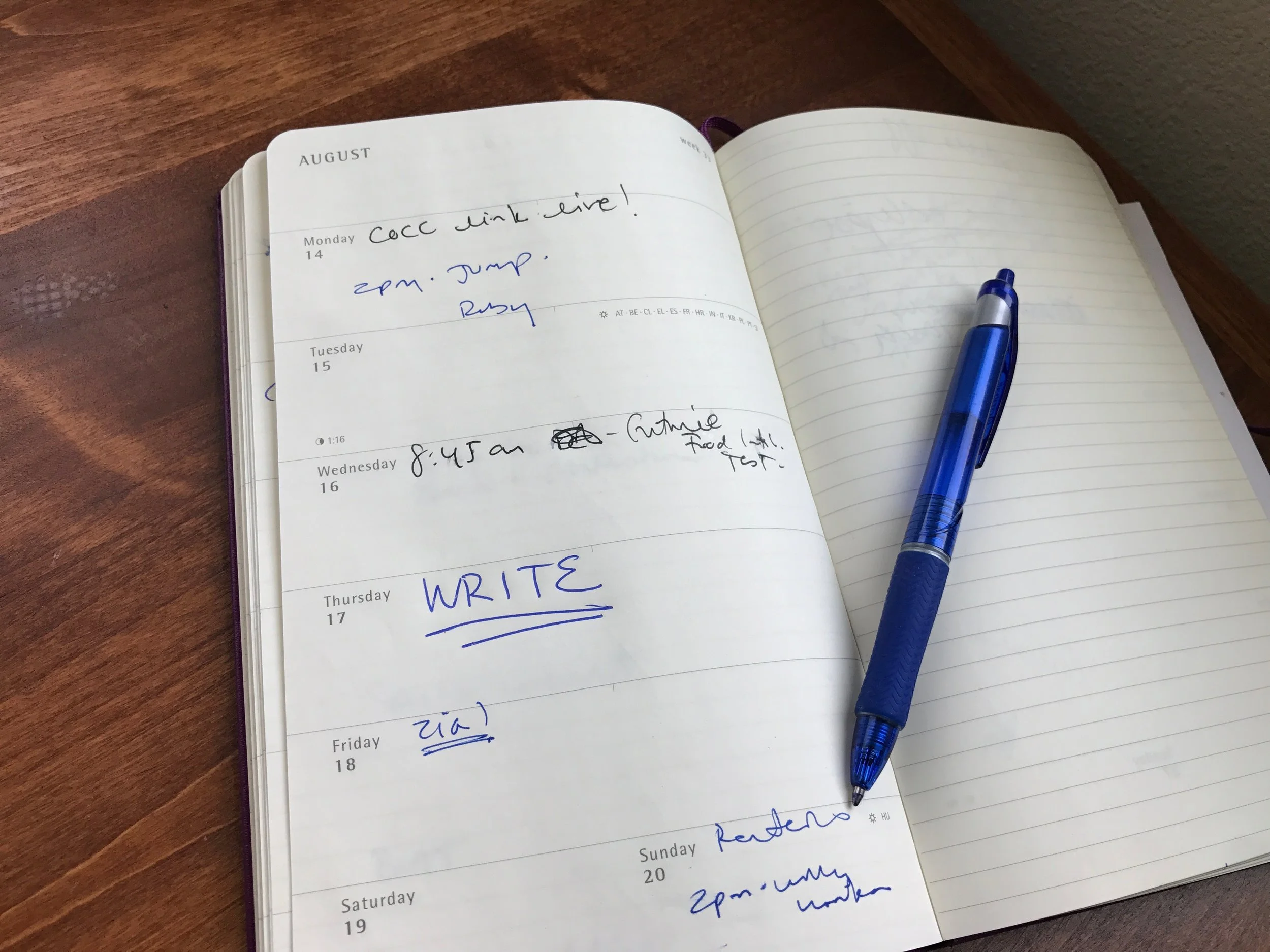

Getting tossed away means not practicing. What tossed away looks like for me.

Viewing entries in

Writing Lesson

Natalie Goldberg introduces the prompt I'm looking at or the variation what's in front of you in every one of her books on writing. Practicing this skill - writing what's visually around you - sets yourself up to use unique, specific detail in your prose. I keep this prompt in my back pocket and use it several times a week, particularly when I've scheduled myself time to write but feel ungrounded.

Thursday, 6:20 AM, for example. My head feels detached from my body. I am in my car. It is running. When I left the house, stars still blinked in the sky. I start to paint with words the way the barista is preparing to open the coffee shop on Newport Avenue in the darkness, his broad shouldered silhouette moving back and forth along the bar, the only light a fat Edison bulb in a square wooden lamp.

I see evidence of this prompt in use by authors I admire. Whether they are conscious of it or not, I don't know. Case in point:

An excerpt from Terry Tempest Williams' When Women Were Birds:

I am in jail because I was speeding, driving under a suspended license.

I am in jail because I didn't have the money to pay the fine.

I am in jail because one night can't be that bad.

I am in jail because part of me thinks I deserve to be.

INSIDE

Three sets of doors open and close behind me, then lock shut. I enter the women's pod, where twelve prisoners like myself are dressed in orange. It is a crowded room, with seven metal bunk beds; a toilet, sink, and shower; and four bolted-down tables with attached chairs that swing out from under them. The walls are cinder blocks painted white, with no windows, only fluorescent lights. The floor is covered with shiny linoleum squares.

-

Seems as though TTW asked for a pen and paper in her jail cell. Practice what I'm looking at // what's in front of me wherever you find yourself: car, prison, or otherwise.

Photo by Robert Hickerson on Unsplash

On nights when I jot a few ideas down in a notebook or listen to a Moth podcast before heading to sleep, I wake up the next morning with a writing frame of mind. Words form quickly and I face less resistance to write.

The feeling spills over into my day. I record a line of conversation I hear at a cafe. I note the empty wire shelves at my local hardware store, a sure sign of the culmination of summer and an image I want to weave into a poem that's slowly forming.

Writing begets writing. Do more of what cultivates writing in your life. Shed what doesn't.

What happens when we focus on commonplace objects in writing?

Some thoughts on keeping the pen hitting paper on a consistent basis.

Sometimes when I write I get this feeling that I know where I'm going. There's a momentum to tie things up in a bow. A pull toward closure or an answer. If I keep down this path, the piece would read like a Hollywood Blockbuster: predictable, formulaic. Spoon fed, boring.

Writing practice isn't easy to explain.

Natalie Goldberg calls it monkey mind. Steven Pressfield labels it resistance. Elizabeth Gilbert describes it as fear. Regardless of the name, the concept is the same: it's the thing that stands in the way for so many of us wanting to accomplish a writing goal.

Your life, in six words.

Be specific. Not tree, but ponderosa. Not sandwiches, but corned beef. How do we teach ourselves to write with more specific detail?

When you hit the road this summer, take writing practice with you. Here's how.

I like to call writing practice writing into the abyss. It is an act of faith. Day in and day out, you put pen to paper, without any guarantee of results, just like a young Olympic hopeful.

This theme - writing to discover - continually surfaces among creators that I admire.

Verbs bring energy to a sentence. You don't need to ring your hands on every verb, of course, but sprinkling some eyeball-stoppers here and there will invigorate your work.